“I know what that shout means among the children,” said Miss Amy; “the Miscellany has come.” So I ran down stairs and saw Papa with the book in his hand, stooping down to Mary, who was stretching up her neck, and Emily, who was standing tip-toe to get a look at it; while little black Dinah showed her white teeth for joy.

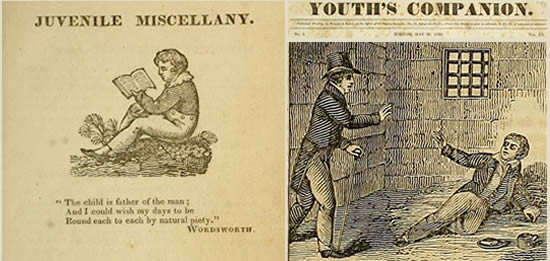

Juvenile Miscellany, November 1829

Working at a time when the Sunday school magazine was flourishing, Lydia Maria Child took a different approach to writing for children. Rather than focusing on Bible studies and religious lessons, she combined moral teaching with entertainment in the Juvenile Miscellany.

In the first (September 1826) issue of the magazine, Child explained her editorial philosophy and approach to her young readers:

I seldom meet a little girl, even in the crowded streets of Boston, without thinking with anxious tenderness, concerning her education, her temper and her principles… . You, my dear young friends, shall be my critics: If what you find neither affords you amusement [n]or does you good, I shall think it badly written. If I am able to convince you, that you can do, whatever you try to do, in the acquisition of learning; if I can lead you to examine your own hearts … I shall be very happy.

Not everyone in Boston was pleased with this new idea. In response to Child’s lack of an explicitly Christian focus, six months after the first issue of the Juvenile Miscellany was published, Nathaniel Willis, a well-known Boston editor, began publishing the Youth’s Companion. As he explained in its prospectus, this magazine would not be like others that “excluded religious topics” and were for “mere amusement.” Instead, it would give priority to “articles of a religious character.” Thus began the clash between these two popular publications. In every way—from the subjects considered to the vocabulary used—these two editors attempted to provide their young readers with different experiences, different kinds of lessons. For example, even natural history articles served different ends. A discussion of the elephant that appeared in the July 1829 issue of the Juvenile Miscellany described the animal as “the most intelligent of all brute creatures … and the kindest.” An article on the same creature that appeared in the August 1827 issue of the Youth’s Companion compared it to “the behemoth mentioned in Job 40:15.” Ultimately, the competition between these two magazines—their sharply different senses of what their young readers needed—set the stage for a much broader discussion of educational goals and methods: how and what, in this era of change, children should be taught.